Column

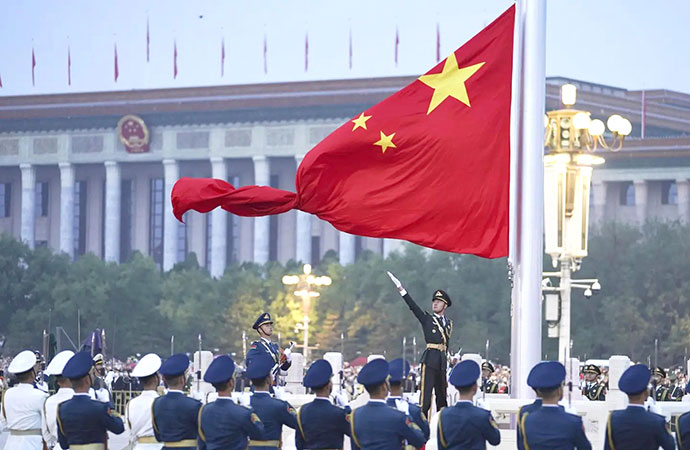

Members of the People’s Consultative Assembly stand as the national anthem is played during the swearing-in ceremony of Indonesia's new President Prabowo Subianto at the parliament building in Jakarta, Indonesia Sunday, Oct. 20,2024. Photo: AP/UNB

The outbreak of unrest in Indonesia is an obvious reminder of the protests that occurred in Bangladesh last year. Indeed, events across the Indonesian archipelago uncannily mark the first anniversary of the Bangladesh Revolution. But are the two occurrences the same? Is this a Banglanesian - a neologism that means Bangladesh Plus Indonesia - moment in Asian politics?

Perhaps yes. Bangladeshis and Indonesians are both people and what happens in one nation affects another viscerally. This is largely true of the entire world, where issues such as endemic economic inequality, entrenched political inequity, the ritual misuse of the state's repressive apparatus, and the sly consolidation of the governing class's privileges and prerogatives incense public opinion over time and require just one straw to break the camel's back. Reservations in scarce public-sector jobs provided that proverbial straw in Bangladesh; abnormally-high housing and other allowances for parliamentarians did the same in Indonesia among citizens battling the rising cost of living. In both Bangladesh and Indonesia, an incendiary moment was created by injustices created and sustained over time. One day, people said: Enough is enough. It is time for change.

Yet, is this a Banglanesian moment after all? Perhaps not. The primary reason is that the Awami League fell after 15 years of continuous rule (preceded by earlier periods in the contested legitimacy of power) in which its promises had turned to dust and its abuse of power had graduated from the tolerated exception to the intolerable norm. Questionable national elections (to say the least) legitimated - not legitimised - regime survival among a citizenry that lacked meaningful parliamentary representation. Corruption went from being a dependent variable to an independent one. External intervention in national politics - never absent in Bangladesh, and from many quarters - became internalised. Bangladesh began to slip from Bangladeshi hands, or so it seemed. We know the rest of the story, till now at least.

Indonesia is different. It has been through worse moments than Bangladesh. A failed communist insurrection brought down the ideologically-inclusive regime of founding President Sukarno (1945 to 1967) and unleashed a bloodbath that helped to install the anti-communist General Suharto in power (1967-1998). Suharto modernised Indonesia by making it a bastion of capitalist development guided by the military's iron hand. The Asian Financial Crisis brought down the dictator, allowing Indonesia to embark on the democratisation of political life.

General Prabowo Subianto, a former son-in-law of Suharto whose military career was marked by accusations of human-rights abuses, is now President as part of the democratic process, but he is seen by many as seeking to militarise civilian life so consolidate his grip on power within that process. Meanwhile, Parliament has gained life and momentum since Suharto's downfall, but democratically-elected politicians have become a political class unto themselves. (Sounds familiar?) Their obscenely-high housing and other perks sparked the current round of protests, which turned violent after a delivery rider (who was not even a part of the protests) was killed by a police tactical vehicle. Violence spread from Jakarta to the provinces. For the first time in democratic Indonesia, mobs looted the homes of several parliamentarians and of a minister, no less.

The government has retreated on the parliamentary allowances and promised to give justice to the slain delivery rider.

However, the structural roots of violence, whether carried out by the state against the people or the people against the state, remain unaddressed.

That structure has everything to do with the aftermath of decolonisation. (Indonesia won its independence from Dutch colonialism, followed by Japanese imperialism, in 1945.) In an iconic publication, "Old State, New Society: Indonesia's New Order in Comparative Historical Perspective", the Cornell Indonesianist Benedict Anderson overturned the familiar trope of decolonisation having produced new states that presided over old societies. Instead, he noted the persistent paradox of postcolonial old states coming to preside over new societies, where decolonised states pursued internal and external policies resembling those of their colonial predecessors against the needs and wishes of the new societies that had been produced by the anti-colonial struggle. The Dutch colonial state, roughly 350 years old, was tested to the limits by the Japanese invasion of 1942. Sukarno sought to create a new society within the shell of the old state that he had inherited, but he failed. Suharto reverted to reinventing the state as something new and in charge of an old society that needed to be modernised. It could not be, because democracy is the only way to do that, and Suharto was an instinctive dictator.

Today, President Prabowo has an opportunity to set Indonesia on a new path. Indonesia is a new society - it has been one since Sukarno's time - but an old state has survived decolonisation in 1945, no less than eight decades ago. Democratic ritualism - the coming to power through elections - will not do by itself. It has to be accompanied by civic emancipation: the right and the responsibility of every citizen to be invested in the lives of fellow-Indonesians. It is difficult to believe that his military past will allow him to do so easily. But it is not impossible to believe that a thinking ex-General like him (which is why he is President today) will acknowledge the reality of Indonesia as a new society that has tired of the old Dutch/Japanese/Suharto state. He can still turn history around. He should.

President Prabowo has introduced several pro-people policies. Chief among them is the introduction of the free mid-day meal for students, which is a material attraction for poor parents to invest in the education of their children. Friends of Indonesian society would welcome this state intervention: This is how people in power should come to terms with poverty among the people. He should continue with such programmes, with a careful eye on fiscal sustainability of course. But he should continue with policies that alter the balance of power between rulers and the ruled, in the latter's favour.

President Prabowo's military past is less important than his popular future.

Protests come to pass, but something has to change in the process. In the realm of Banglanesia.

The writer is Principal Research Fellow of the Cosmos Foundation. He may be reached at epaaropaar@gmail.com

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Religion and Politics: A Toxic ...

At Dhaka University, cafeteria workers have been told not to wear shor ...

Enayetullah Khan joins AsiaNet ...

AsiaNet’s annual board meeting and forum was held in Singapore, ...

In a New York minute

Many leaders back a UN call to address challenges to ..

Defaulted loans at Non-Bank Financial Institutions ( ..

How the late Zubeen Garg embodied cultural affinitie ..